Where do the mixed girls without minjok go?

On Black-Korean Adoptees, f*cked-up beauty standards, and the Third Space

Listen first —

A short voice note about why I wrote this. You can skip it… But maybe don’t.

This essay began as a Thread.

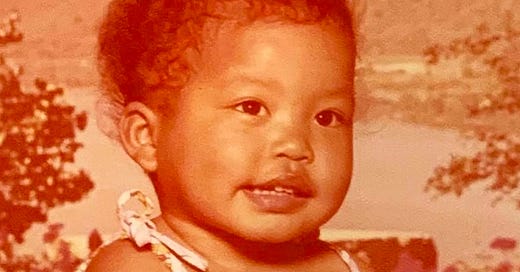

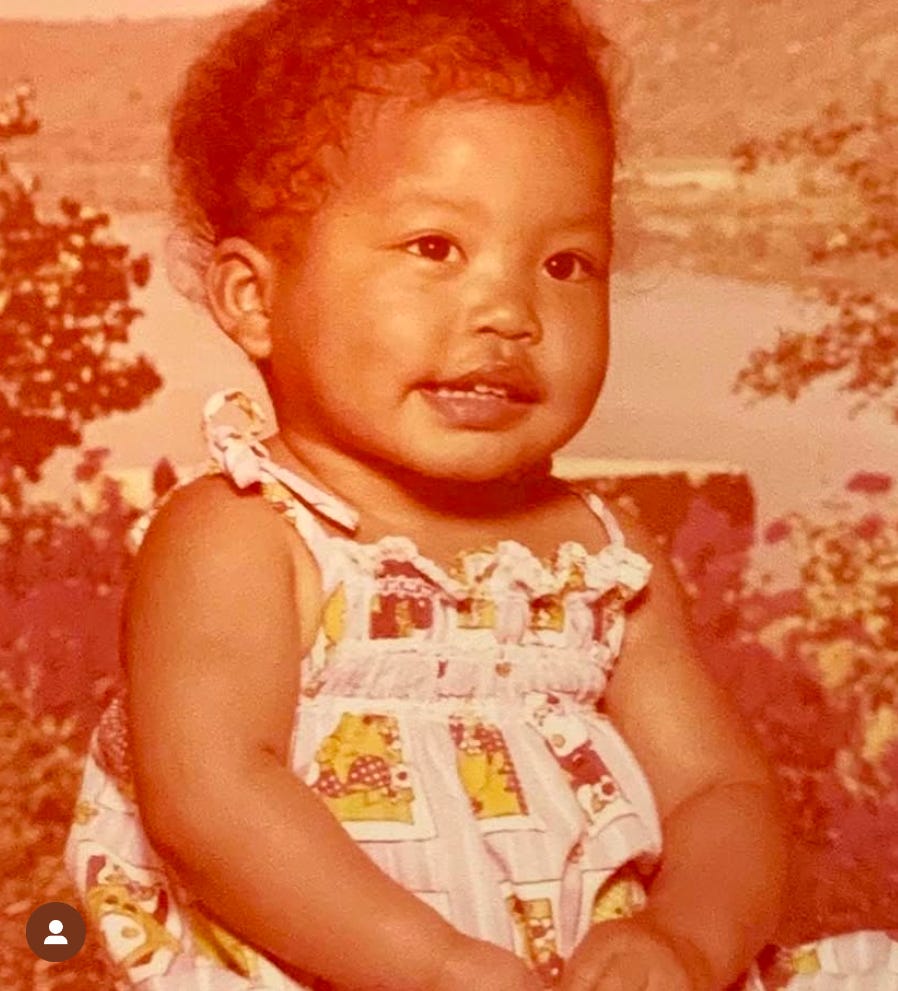

I was doing research (which prompted me to post a Thread) on the mixed-race children of Korean women and Black American soldiers in the 1970s and 80s. I know, super specific, right?

I’m writing a piece on Black & Korean identity - researching how mixed-race kids of Korean women & Black American soldiers were treated in the 1970s & 80s. My lack of “minjok” (purity of bloodline) & the anti-Blackness sentiment are probably the reason I was abandoned. I wonder how my life would’ve been different. I read a book that gave me a glimpse- “The Fox Girl” about a Black & Korean girl who was sent to a “throw away” school in Korea because she was the daughter of a Black American soldier.

I didn’t expect much engagement—after all, my experience feels so niche. But I was wrong. People had feelings. They could relate—Black and Korean adoptees, their relatives, friends, spouses, and co-workers. The replies not only validated my experiences but illuminated a collective one. We’re out here. Even though I couldn’t find you in the 1990s, I forgot to check back in once the Internet became a thing. My bad.

So here I am, late to the party. The overwhelming responses revealed something I hadn’t fully grasped before—a sense of community. I wasn’t alone in feeling like I’ve been navigating these liminal, hyphenated spaces all my life. One poster wrote,

This is so needed. Sending you all the best with research and will follow to read. (As a Korean adoptee raise in an all-white rural Maine town and realized how I would never be American and never be Korean.)

And another:

Have someone I worked with that was born in 1970 in Korea. Dad was Black a soldier mom was Korean. She was in an orphanage & adopted out at the age of six months. She has no knowledge of who either of her parents are. Has a few of her things that were left with her and from what she gathers she was not wanted. She’s been to Korea once but with no luck and has decided not to pursue it anymore.

These responses not only affirmed how I was feeling but also got me thinking about how identity exists in these complex, in-between spaces. That ultimately led me to the idea of the third space—a concept I was introduced to in grad school that helped me make sense of/articulate my own identity. Third space—a term coined by Homi Bhabha, is a creative space between conflicting cultures where people can negotiate meaning and resist dominant ideologies. It’s a ‘gathering place’ where different cultures, ideas, and identities come together, and commingle, to create something entirely new. This quest in creating the space is both deeply personal and collective, offering an opportunity to critique, resist, and ultimately reshape the boundaries of how you see yourself and your identity. I felt like I had just discovered a new third space.

Historical Context

In sharing my own story, it’s important to examine the historical forces that shaped the experiences of mixed-race children in Korea. The Korean adoption system set a precedent for the large-scale, government-supported export of children to adoptive families in other countries, particularly the United States. For mixed-race children, especially those with Black fathers like me, adoption served as both a financial tactic and a means of erasing what society deemed undesirable.

Korea’s adoption policies were shaped by a complex mix of humanitarianism and Cold War politics. American adoption agencies, like Holt International, worked closely with the Korean government to facilitate the exodus of more than 200,000 children—70% going to the United States. Agencies often pressured Korean mothers into giving up their children, exploiting societal stigma and economic hardship. The system wasn’t just about placing children; it was about maintaining minjok and upholding Confucian values. For the U.S., adopting Korean children reinforced its global benevolence and alliance with Korea, while for Korea, it was an expedient solution to internal social issues. This partnership, however, was not just about finding homes—it became a lucrative, transactional system.

Adoption agencies acted as brokers, turning children into commodities. Foreign families paid high fees to adopt, with the Korean government reaping the financial benefits while minimizing its welfare obligations. Mixed-race children, especially those of Black descent, were seen as less “marketable” and often had lower adoption fees, reflecting the deep intersection of anti-Black sentiment and the commodification of children. Adoption wasn’t just a solution; it was a method of cleansing the racial and cultural landscape. Despite being framed as a compassionate act, the system was driven by economic exploitation and societal pressures, feeding what became known as the adoption industrial complex.

Minjok & identity

Adopted at the age of two by a White couple in the Midwest, I’ve spent much of my life grappling with questions of identity and belonging. Growing up Black and Korean in a predominantly White, rural town shaped much of how I saw myself and how others saw me, as I navigated the intersections of race, disability, and beauty standards.

I think it’s really important to say before I go much further, there are a multitude of extenuating circumstances that would compel a young woman in 1970s Korea to give up their child born out of wedlock. I am not trying to reinforce some master narrative that minimizes this to being “too Black” because in addition to minjok and anti-Black sentiment, there was a whole lot of cultural stigma, limited resources, and pressure from adoption agencies to feed the K-Adoption Industrial Complex. While minjok and anti-Black sentiment played critical roles, they were intertwined with a larger system of patriarchal, nationalist, and class-based oppressions that shaped the experiences of single mothers and their children.

I went to a Korean Adoptee camp for most of my childhood as a sister to a korean adoptee. A common story from the older adoptees and even the counselors who were Korean immigrants was how black/korean mixed kids were spit on when they were playing outside at the orphanage. This story was common and was usually brought up as an example of how people could pick and choose values from their multicultural experience. Many young Korean immigrants deeply valued America's "lack of racism".

You can see how it plays out in the real world. It isn’t just an abstract concept—it permeates everything, including Korea’s beauty standards. In Korea, it’s all about homogeneity—pale skin, narrow noses, and sleek hair became cultural markers of purity and belonging. For children like me, who were born into the liminal spaces of these cultural expectations, beauty standards weren’t just personal preferences but markers of exclusion. Growing up, I internalized the idea that I didn’t fit in either here or there. My physical appearance—darker skin, different features—was an immediate signal to others that I was not fully Korean, not fully Black, and certainly not “beautiful” by Korea’s rigid standards.

Additionally, Confucianism—deeply embedded in Korean society, emphasizes filial piety, family honor, and the preservation of social harmony. I mean, seriously, who can live up to all these standards? For single mothers in 1970s Korea, giving up their children, especially those born out of wedlock, was often seen as a necessary sacrifice to protect family dignity and avoid social disgrace. This alignment with Confucian ideals—prioritizing family reputation over individual well-being—shaped adoption policies that not only promoted racial homogeneity but also served to preserve a social order rooted in Korea.

As a result, I, and others like me, were pushed to reimagine our identities and carve out a space of our own (different for everyone). This process of redefinition ushered us into Bhabha’s third space.

We exist at the intersection of Korea’s obsession with racial and cultural purity and their pervasive anti-Blackness sentiment. Rejected by mainstream Korean society, we inhabited a “third space” of identity formation.

As my identity shifted, so did the lens through which I understood beauty—not as neutral or harmless, but as deeply political. Beauty standards, then, are not simply aesthetic preferences. They shape who is accepted, who belongs, and who is invisible. For those of us living in the third space, these standards provide both a challenge and an opportunity: to resist, critique, and redefine the boundaries of beauty and identity on our own terms. What was once a barrier to my identity became a point of pride. The shift in how I was perceived—from marginalized to valued—was transformative, leading me to finally find a sense of belonging.

Mixed-race Black and Korean kids, shaped by societal rejection and in-between identities, develop a unique perspective that challenges and deconstructs rigid ideas of race, ethnicity, and culture. We exist at the intersection of Korea’s obsession with racial and cultural purity and their pervasive anti-Blackness sentiment. Rejected by mainstream Korean society, we inhabited a “third space” of identity formation. In this space, people negotiate who they are—adapting, resisting, and self-creating—moving beyond an “us” and “them” binary.

Picking sides

Minjok shaped how I viewed myself as an outsider in both Korea and America. Even though I was raised by White parents, I still felt the sting of rejection when I told other Koreans I, too, am Korean; when I saw how Blackness performed as rigid, binary, confining and how my difference spilled over the edges; or when White classmates made racist jokes that weren’t about me because, I was ‘different’ but I couldn’t help feeling small and ugly but also really angry. I carried this uneasiness for years, unsure where I fit or belonged.

By my sophomore year in high school, I was firmly grounded in my Blackness, rejecting the cultures that had rejected me. At the same time my identity was solidifying, it was complicated by the contentious relationship between Black and Koreans — starting with tensions of the Watts riot in 1965, followed by the LA Riots, a result of Rodney King beating in 1992.

The general sentiment was Korean folks owned all the beauty supply, liquor, and convenience stores in Black neighborhoods. Black residents, who’d been excluded from economic opportunities due to systemic racism, often felt alienated from the ownership and control of their local economy; their own neighborhoods. Meanwhile, Korean shopkeepers saw these neighborhoods as affordable areas to build a business but often lacked the cultural knowledge or resources to engage with and build strong ties with the Black community. My two identities were literally at war with one another; in many ways I felt I had to choose.

Black culture was having a moment—Public Enemy was fighting the power and seeing Janet Jackson in Poetic Justice reinforced the notion that Black girls can show up differently; I just needed to understand who I was and be grounded in that. I went through a process of self-creation—Cross Colors, bamboo earrings, chocolate lined lippies, and box braids ala “Poetic Justice.” In embracing these elements of Black culture, I not only found a sense of belonging but also began to redefine myself on my own terms, no longer constrained by the identities others had imposed on me.

I can’t say I was free from the identities others put on me—I wasn’t. I made a choice, but it wasn’t fully mine. It was survival, a way to belong in a world that demanded I pick a side.

Only later did I realize I could be fully Korean, fully Black, and most importantly, fully whole.

To understand this shift in perception, anthropologists like Arjun Appadurai provide a framework to explore how value and identity are constructed across different cultural contexts. In his concept of the tournament of value, Appadurai explains how meanings are not fixed but are negotiated and redefined in social spaces. I realized that identities and attributes are ranked and redefined in different cultural spaces, and what was once seen as marginal could become central in another. In this social arena, attributes, identities, and even people are ranked and assigned worth based on cultural context, with value shifting dynamically rather than remaining fixed. The very things that were once considered “flawed “in Korea and overlooked or misunderstood in White spaces—my textured hair, my fuller lips, and my darker skin—were now celebrated in Black spaces. This shift in perception, from marginalized to valued, transformed the way I viewed myself.

This shift didn’t erase the struggles of being bi-racial, but it gave me a platform to assert myself in ways I never had before. I had transitioned from being marginal to being celebrated, moving through a tournament of value where my identity was finally placed in a space where it could shine.

For a deeper dive into this concept, watch Arjun Appadurai: Commodities and the Politics of Value.

Identity be shifting.

My time at Clark Atlanta University exemplified the transformative power of the third space, where new dimensions of Blackness and mixed identity could flourish. Even though this was primarily a Black space, there was room to expand the definition of Blackness simply because you existed; you were there. Not having my Blackness in question allowed me the freedom to explore my Korean heritage without negotiating my Black identity. Rasta, Hip Hop, Rock n Roll. King’s English, Nigerian accent, Southern drawl. Natural, locs, press n curls. It was all love.

I met my play brother, Clifton in the AUC (Atlanta University Center a consortium of colleges and Universities—Spelman, Clark, Morehouse, Morris Brown, and the Inter-theological School.) He was the first other Black and Korean person I’d met in my life; I just knew that I belonged. It was also the first time in my life, being in the AUC, that I didn’t worry about being ‘too this’ or ‘not enough of that’—the way I talked wasn’t perceived as ‘too White’ or ‘too proper, just a result of my experience.’ The stereotypes defining Blackness were disrupted at every turn. I’d found my people including my husband of 25 years and my best friend of almost 30.

At Clark Atlanta, I didn’t just meet people—I encountered diverse ways of being Black, mixed, and human. Clark Atlanta was more than a historically Black university; it was a dynamic space where Blackness was constantly being defined and redefined. Here, my mixed heritage wasn’t a contradiction—it was an expansion of what Blackness could mean.

For Black and Koreans, third space might look similar or completely different. Some grew up in urban centers with strong Black communities, while others, like me, navigated rural, White environments where race and identity were constantly questioned. Despite these differences, the common thread is the rejection of rigid constructs and the creation of identities that transcend boundaries. The Third Space is fluid, dynamic, and transformative, emphasizing process over permanence. In other words—identity be shifting.

Ongoing negotiations

As beauty standards continue to shift, so do the spaces where we navigate and redefine who we are. What used to feel like fixed categories—race, culture, appearance—are starting to open up, making room for more fluid, layered expressions of identity. Third spaces—those in-between places where we’re free to show up without being boxed in—are becoming essential to how we understand and express ourselves. These spaces, much like the lived experiences of people who carry multiple identities, challenge us to move past the outdated ideas that have limited our sense of belonging. They invite us to rethink beauty in ways that reflect our full complexity.

In these co-created environments, hybridity isn’t something extra—it’s the foundation. It’s not a flaw to fix or a contradiction to resolve. It’s the very thing that gives us the power to redefine ourselves on our own terms. This space, this third space, is where people like me—once deemed throwaways, once invisible—start to see ourselves clearly. It’s where our stories stop feeling niche and start feeling necessary. Where identity is no longer a rigid script handed to us, but something we write for ourselves. And maybe, just maybe, that’s the beauty of not fitting in neatly—of spilling over the edges. We were never meant to be contained.

Continuing the conversation:

1. How has your own identity shifted across different spaces or contexts, and what role has cultural perception played in that evolution?

2. In what ways can we create more “third spaces” where multiple identities can coexist and be celebrated without the pressure to conform to rigid categories?

Mia, this is wonderfully personal and deeply illuminating essay for me. I can never understand the feeling of displacement, never belonging, and having to "pick sides" in the way that you have experienced in your life, and I hesitate to say this as I don't want to take away anything from your experience, but have felt all of those things in my own struggle as an early immigrant who also came to the U.S. as a toddler. I avoided going to Ktown for decades because of that shame and being treated so poorly because I didn't speak the language (It's all turned around of course because of the popular globalization of Korea in the last 5-10 years). Perpetually treated like a foreigner here in my own country. It's always been an unsettling space to inhabit. Surpringly, when I went to Korea 2 years ago for the first time in 40 years, I did not feel like an outsider the same way I did when I went when I was ten. The feeling of belonging and getting in touch with where I came from was so overwhelming.

All of these stories are so important to share. Thank you for sharing yours.

Thank you for sharing your journey with clarity and choosing wholeness against social pressures. You story gives more space for being.